Imagine being able to walk outside to your backyard for a natural fix for that acne you’ve been dealing with, or that relentless cough you’ve had for weeks that just won’t go away. What if you could go out back and dig up an herb to clear your sinuses and relieve your allergies? If you lived in the golden days of Appalachian heritage, almost all of your pharmaceutical needs came directly from nature, not from the local Rite Aid.

As a millennial who has obviously conformed to the fast-paced world around me, I’m not one to think about the way things used to be, the way people used to live and survive. I’ve never had to worry about staying sick with no relief, because I can call my doctor, or take a trip to the emergency room, worst case scenario. This wasn’t a luxury available to those in the culturally rich Appalachian region many decades ago. If they wanted to survive, they had to find or create their own solutions for illnesses, and so they did.

This practice is seemingly long gone today with a robust health industry and life expectancy rates increasing almost yearly. But, Appalachian remedies are certainly not obsolete. In fact, those with deep Appalachian family roots are making a real effort to ensure these invaluable remedies don’t fade with the rest of the culture that used to make the region so influential before poverty and economic crisis hit like a tornado.

“Before this region was settled heavily, there weren’t doctors, teachers, and preachers on every corner, but we survived,” said Jamie Jackson, a West Virginia teacher, Appalachian Studies graduate student and self-proclaimed cultural heritage preserver. “(Our heritage) survived thanks to the ingenuity of the Appalachian spirit and a willingness to learn and accept things unfamiliar to us with grace and thankfulness.”

Jackson recognizes that she is in no way, shape or form an expert on this subject, but has dedicated her heart and a great amount of time to understanding and experiencing the way her ancestors lived their lives. Growing up on the Fayette/Kanawha County line, she waded in creeks, dug for night crawlers, chased lightning bugs and watched deer roam the countryside.

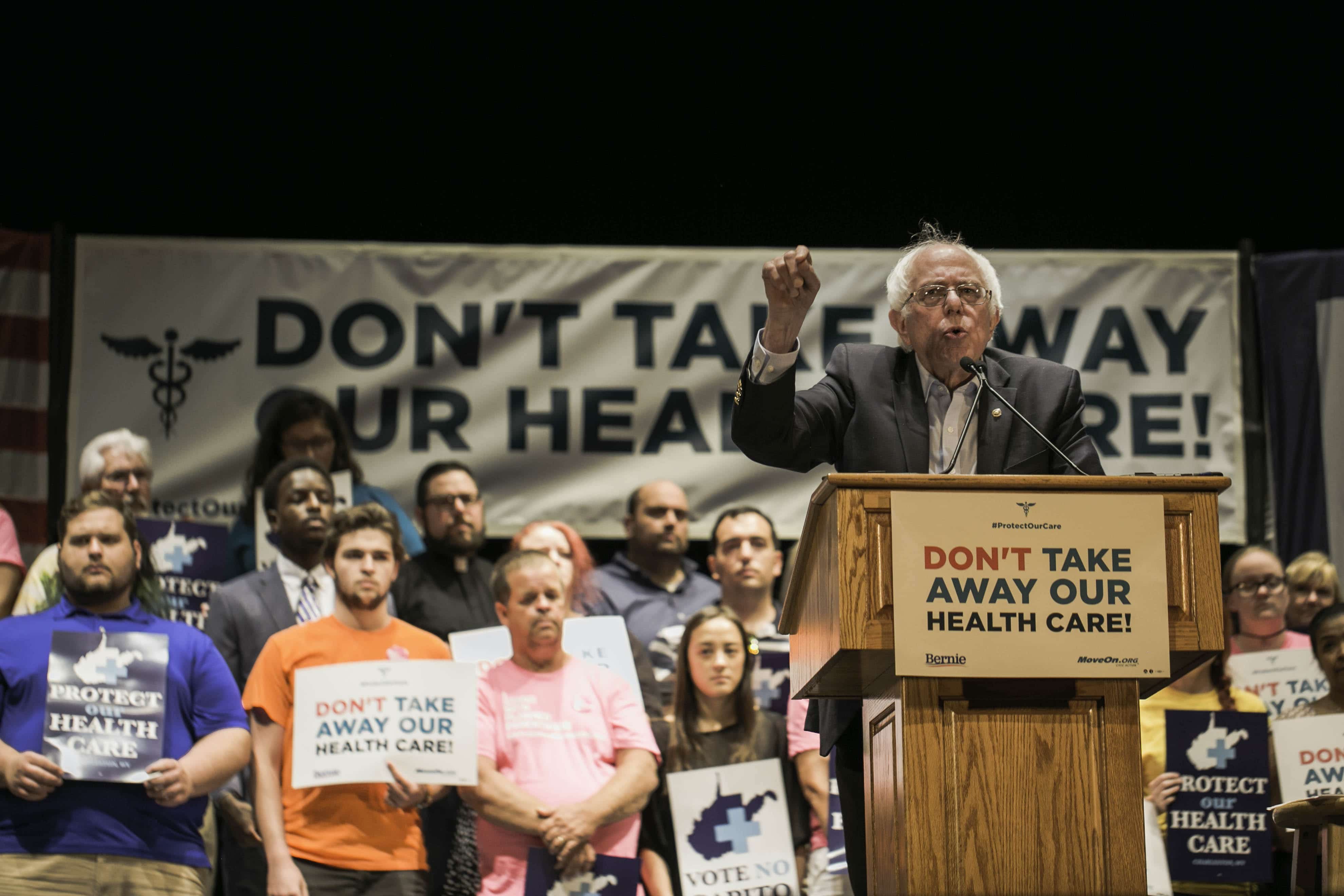

“There is so much beauty in our state and it makes me angry to see how we are portrayed in the media as inbred hicks with a complete lack of education or understanding of anything beyond these hills and the coal lying beneath them,” she said. Jackson referenced JD Vance, an author born in Kentucky, when getting the point across that the rest of America doesn’t necessarily view the Appalachian region or its people as a success story. According to Vance’s official website, his New York Time’s best-selling book Hillbilly Elegy “tells the story of what a social, regional and class decline feels like when you were born with it hung around your neck” and depicts his family’s move out of the Appalachian region as an escape from dreadful poverty, eventually allowing him the opportunity to achieve their “conventional marker of success in achieving upward mobility” by graduating from Yale Law School.

“To me, our cultural traditions are beautiful and artistic, in touch with the Earth using a bit of whimsy and a lot of grace; absolutely deserving of preservation,” Jackson said.

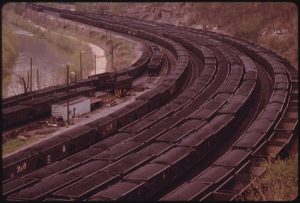

For West Virginians specifically, living in a state deemed the third-poorest in America in 2016, Appalachian’s old fashioned ways could come in handy right about now. The decline of coal — an industry that has allowed many states in the region to thrive and survive decently well over the past few decades — has slipped off. The economy continues to suffer, and Jackson can only dream about the way things would (and could) be if more people took the initiative to learn about simple and scarcely practiced Appalachian medicinal remedies and a healthy food culture that disappeared with the uprising of processed foods.

“People stopped fixing things, opting to replace them instead since they had the money (from when the coal industry began to boom),” she said. “Gardens went to seed as stores offered produce at a rate that negated all the hard work of plowing and harvesting. People began to hunt for sport instead of food, a disservice to both our bodies and animals. Processed food, heavy with chemicals, became the standard in households where dinner had previously come from the backyard. It seemed coal would never die and that the money that came with it was an endless well. But it wasn’t. As coal declined, so did the money.”

The Appalachian way began to evaporate. People didn’t know how to make the most out of nothing anymore.

Homespun remedies aren’t popular today because there’s a reliable cure for just about anything that can be purchased. The problem with that? A majority of West Virginia — and other Appalachian states — can’t afford to keep up. The Mountain State is one of the most troubled when it comes to health problems, ranked as the second most obese state and the second most diabetic state in the country. Jackson is a firm believer that trying your hand at traditional Appalachian remedies and/or growing your own fresh fruits and vegetables and following a healthier, cleaner and more natural diet can be a step in the right direction for those looking to live a nourished, and less costly, lifestyle.

“Moving toward a diet rich in fresh, local produce; lean meat; and very little processed sugar or flour helps combat these problems — a diet much like our grandparents and great-grandparents ate from their gardens, hunting, fishing, and foraging,” Jackson said. “In all our advancement, we lost a few really important ideas and I’d like to bring them back to help Appalachia thrive, regardless of economic ups and downs.”

Jackson started her own blog, Four Strings & a Dogwood, dedicated to “exploring Appalachian folklife through song and cultural tradition”. There, she details her personal experiences with making traditional medicinal remedies like calendula salve (used to heal cuts and scrapes) and wild cherry bark cough syrup, as well as her kitchen adventures learning to prepare naturally grown foods like ramps and collard greens in unique ways.

Thanks to cultural preservers like Jamie Jackson, it’s clear that the Appalachian aliment and medicinal culture (among other parts of the heritage) isn’t dead. The abandoned traditions of this 13-state, 205,000-square-mile region just might improve your way of life.

“The cuisine and arts of Appalachia are seeing resurgence in popular culture, even as the people who give these gifts to the world continue to be maligned,” Jackson said. “But there are those of us living here who are determined to shift that narrative through the arts, culture, and music of the mountains to show the world the true beauty of our region.”